This is a story about war and friendship, memory and loss and a passport.

This is a story about war and friendship, memory and loss and a passport.

We left Beirut at 5:00 in the morning to begin the journey to Latakia, Syria. We had come to meet the Armenians of Kesab, spend time with them, find out about the evacuation and in that process, try to understand what the fate of Kesab might be.

The stories from that 14-hour trip will reveal themselves over time. Some need to be told at once, others will take much longer to digest and develop.

For almost three weeks now, the future of the Armenians of Kesab remains uncertain. After a rebel attack on their village in the early hours of March 21, 600 Armenian families, in a mass evacuation fled to Latakia. Many believed they would return to their homes in a matter of hours, at most in a matter of days. Most left with the clothes on their back, and not much else. Those days have now stretched into weeks. Some have temporarily rented apartments in Latakia, some have gone to Beirut and Anjar and some continue to be sheltered in the St. Asdvadsadzin Church.

The evacuation of the Armenians of Kesab has touched a raw nerve and has brought back memories of repeated displacement and loss.

A quiet veil of depression is slowly creeping in. The elderly, who have been ripped from roots stretching back a millennia sit on plastic chairs with despondent faces. Children of all ages play games under a brilliant afternoon sun, casting shadows here and there unaware of the implications of this seemingly blissful co-existence in a church. Mothers tend to the laundry, volunteers prepare the afternoon meal, young men bring in bags and bags of supplies and line them up in a room beneath the church. Middle aged men, most of them farmers, solid and strong on their land, now seem at a loss. Religious leaders from all three denominations are with and among their flock. They offer the Lord’s prayer prior to the meal, they offer assistance to the now-homeless Armenians and they remain in the church with their people.

In the courtyard of the church, I saw Abraham Ghazarian, my husband’s childhood friend and the mayor of the village of Karadouran. I had met Abraham 25 years ago when I had gone to Kesab to spend the summer with my in-laws. Among the many people, friends and relatives that I met during that trip, he had made an impression and I always remembered him with fondness. I saw Abraham again, almost 20 years later, when he came to Yerevan with his wife. He always represented the goodness of the Kesabtsi man and, in the courtyard, he proved that goodness beyond any imaginable measure.

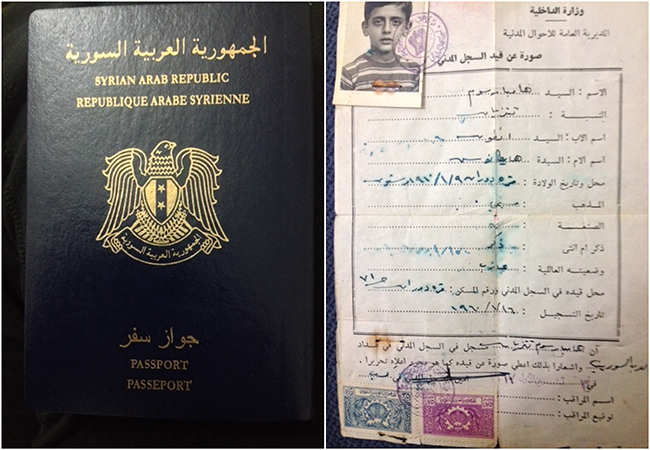

As we were leaving the church to make our way back through dozens of military checkpoints to reach the border crossing between Syria and Lebanon, Abraham came to me and told me he had something to give to my husband. From his pocket, he took out a Syrian passport and handed it to me. I looked at it and then at his face; his eyes were sparkling. I opened it and saw that it was my husband’s Syrian passport. It took a few seconds for me to grasp what was going on. Inside the passport was a forty-year-old document, faded with age and too much folding, with a picture of a little boy stapled on the top left corner. It was my husband’s Syrian ID paper. Abraham had these documents in his home when the rebels attacked.

In the courtyard of the church in Latakia, which hundreds of displaced Armenians now call home, I held in my hand a passport and a piece of paper that might have perished along with other cherished memories, belongings and important documents. While his ancestral village was under attack, while trying to save his family from harm, while leaving behind years and years of labor on his orchards, Abraham remembered to turn back and grab a document of an old childhood friend that was in his trust.

I couldn’t speak, he didn’t need me to speak. All he said was, “Maria jan, I couldn’t leave this behind.”