When the painter Martiros Saryan visited Istanbul in 1910, he was on the verge of entering a highly productive period. He wanted to understand the East, penetrate its soul, and express it in a new artistic form. “I wanted to express the realism of the East and find convincing ways to describe and depict that world, discover its new artistic comprehension,” wrote the artist, who is considered to be the founder of modern Armenian painting.

He stayed in the Ottoman capital for two months and later visited Egypt and Iran. During this period, the artist’s colorful palette was fully revealed in his works on Eastern themes. What caught his attention in the ancient city of Istanbul were “the streets, their rhythm of life, the flamboyant crowd, and the dogs… that used to live in extended packs” as mentioned in his memoir.

Exactly 100 years later, another Armenian artist, filmmaker Serge Avedikian, was also experiencing a productive period. The experienced actor and director won the Best Short Film Award at the Cannes Film Festival that year with his work “Chienne d’Histoire.” The dogs of Istanbul, which had caught Saryan’s attention, also caught Avedikian’s, but in a completely different context.

In his film, Avedikian depicted a tragic event that occurred in 1910, the very year Saryan was in Istanbul. That year, the ruling Committee of Union and Progress decided to round up thousands of dogs that roamed freely on the streets of Istanbul and were an integral part of the city’s landscape, and exiled them to Oxia (Sivri) Island in the Sea of Marmara, where they would be left to their fate.

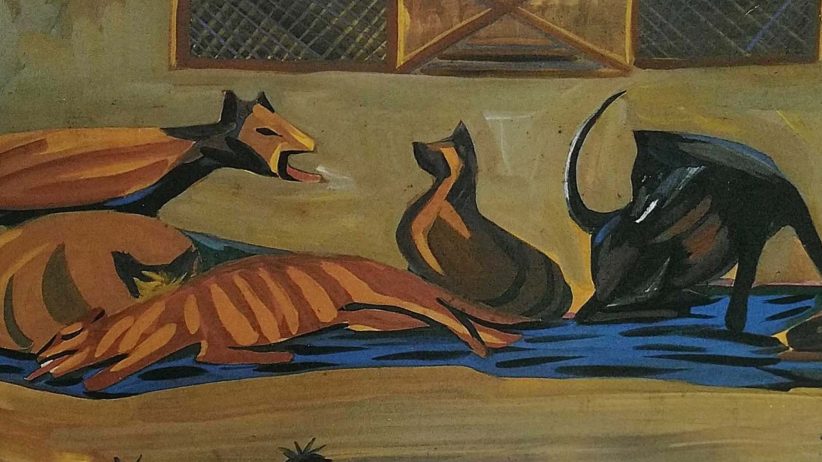

The dogs that attracted Mardiros Saryan’s attention were also a distinctive feature of Istanbul for many travelers of that era. These animals, lounging, wandering, and sunbathing in the streets, were seen as an integral part of the orientalist perception of the lazy, idle, and immobile East. In Saryan’s paintings, we can see them passing by a veiled woman, napping in a shadow, or fighting with each other – as if they were true owners of the city, along with their eternal antagonists, the cats. However, this traditional tableau was unacceptable for the Committee of Union and Progress, the Jacobin revolutionary clique that wanted to modernize the empire, gain strength against the Western states they competed with, and in doing so, needed to achieve a contemporary appearance.

Academic Mine Yıldırım, who works on the subject, states that the travelers who came to Istanbul from European cities, which had systematically eradicated the presence of stray animals, encountered a city where dogs still roamed freely at the beginning of the 20th century and had two main reactions to the “dog-filled city” they saw: a mix of astonishment and admiration, and contempt. Western elites wondered, “How is it that while animals are violently cleansed in our cities, dogs are still protected in the tired city of the East?” They argued that the issue was related to the “primitiveness of Eastern culture.” The discourse of “stray dogs” would emerge during this period, because in the eyes of the political power, dogs became a problem that marred the image of the imperial capital, giving it a decayed and dirty appearance and needed to be eliminated. For the militarist Unionist elite accustomed to holding a hammer, the dogs would become the metaphoric nails.

We do not know how aware Martiros Saryan was of these issues while depicting the dogs with his keen artistic eye, but 100 years later, Serge Avedikian certainly saw the connection between the mass exile and destruction of dogs in Turkey and the Armenian Genocide that would begin five years later. After all, he was also the grandson of the orphaned generations who were victims of the Armenian Genocide in 1915. He understood the meaning of forcibly displacing a group of living beings from their environment, gathering them in one place, transporting them to a region entirely unsuitable for living under harsh conditions, and leaving them there hungry and thirsty. Whether it was dogs or people who experienced this, the result would be disaster and death.

There was no ethical, moral, or conscientious difference between what was done to Istanbul’s dogs in 1910 and what was done to the Armenians, subjects of the empire, five years later. Academic Özlem Güçlü makes the same connection with the words, “The disaster of the dogs in 1910 and the disaster of the Armenians in 1915 are both results of the same genocidal intent, the same public ‘cleansing’ mentality.”

In the 114 years that have passed, Turkish rulers have not put down the hammer, and thus they continue to see everything as a nail. Recently, the ruling Justice and Development Party prepared a bill to round up stray animals from the streets and “to put to sleep” those not adopted within thirty days. Stray animals became one of the key issues in the local elections held in March, with religious and nationalist far-right parties manipulating their supporters and targeting these animals. According to them, there was a major stray dog problem in Turkey; these animals attacked passers-by, causing countless deaths each year, and a “final solution” to this problem was necessary. Videos of dog attacks, many of which did not even occur in Turkey, were constantly circulated on social media, stoking an insatiable appetite for violence by creating a new enemy and prey, sharpening the swords.

After his party received low votes in the elections, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan decided to take action, thinking that this propaganda had harmed them. Believing that the shadows of impotence, loss of power, and inability to govern would have irreversible consequences for him and his rule, Erdoğan ordered the preparation of a draft law heavier than even the ultra-right-wing opposition expected, presenting a step that could mean the mass slaughter of dogs.

However, experts believe that the problem is human-induced, not dog-related. In a geography like Turkey, where urbanization has been rapid and brutal, cities have grown in an unplanned manner, the whole country has almost become a construction site, and natural habitats have been rapidly consumed, dogs that have lived peacefully with humans in cities for centuries face countless problems like hunger, thirst, safety, shelter, and attacks coming from people full of hate against animals. When the problem, which could be solved with a simple spaying/neutering campaign, was postponed for years, a “measure” that meant ultimate violence for dogs has come to the agenda. Another shameful link to Turkey’s history filled with massacres and violence.

The author Sezgin Kaymaz hits the nail on the head of the problem: “You both descend upon their habitats like a nightmare and then name them as if you’ve discovered a new and harmful species, calling them stray animals.”

These days, Israel’s genocidal aggression on Gaza connects with my distress about the fate of the dogs in Istanbul, the city where I was born and where I live. In 1910, when the dogs were exiled to Oxia Island, people thought this would bring a curse and changed the island’s name from “Sivri” (meaning “sharp”) to “Hayırsız” (meaning “ill-fated”). The Ottoman Empire collapsed just twelve years later, after having caused great and many disasters. Can you say it was a coincidence?

Rober Koptaş is a writer and publisher, lives in Istanbul. He served as the editor-in-chief of Agos newspaper from 2010 to 2015 and the general director of Aras Publishing from 2015 to 2023.

Also read:

Eternal Manouchian: To the Pantheon or to the Crowds?

Letter from Istanbul: The Irony of the Armenian Photographer

Letter from Istanbul: Turkish Republic of Impunity

Letter from Istanbul: Towards the Future with Hrant Dink