–

The European Championship has just begun, a kind of ritual that comes around every four years for football (soccer!) lovers. On the streets of Germany, fans from different nations are engaging in playful banter. Albanians are doing what drives Italians crazy, breaking spaghetti in half in front of them, while Austrians carry posters before their match against France proclaiming that pretzels are better than baguettes. Football unites people from all around the world, even those who cheer for different teams, allowing them to feel a sense of camaraderie by speaking a common language – at least for a while. However, it is clear that sometimes even the joga bonito is not enough to express more. Fans often turn to food, and elements that enhance the glory of their national kitchens, engaging in seemingly harmless debates about whose cuisine is better, which dish belongs to which nation, or who invented it first: Baklava, manti, doner kebab, hummus, tzatziki – the list is endless. But are these debates really harmless?

In reality, with some notable exceptions, foods do not have nationalities. Where a dish is cooked often tells us more about the local environment than which nation it belongs to. Geography, altitude, soil structure, and humidity determine what will grow or how it will be preserved, cooked, and eaten. Of course, cultural, social, and political conditions also play their role. Neighboring peoples sharing the same geography often share culinary traditions, while people of the same ethnicity living in different areas eat different things. What we like or dislike, how we prepare and present it, are shaped by cultural preferences and social structures. By examining the differences in eating and drinking habits, we can draw significant conclusions about class, ethnicity, nationality, or gender-related conflicts. Ultimately, everything is political, and like music, clothing, housing, or sports, food is an aspect of social or cultural identity.

Scholar Zafer Yenal points out that the nationalization of food and table culture is much more recent than we might think. Many studies in the field of food sociology and history agree that the idea of a national cuisine mostly emerged with the nation-state formation process. We see that French cuisine, often regarded as one of the most advanced in the world, began to nationalize from the mid-19th century. Research shows that the coding of regional, local cuisines with very different cooking, preservation, and presentation characteristics into a more national menu played a significant role in the formation of “French cuisine” especially with the spread of media or democratization of education. Similar processes likely shaped other national cuisines. Therefore, adds Yenal, just like the concept of a nation, the concept of national cuisine has also been retrospectively “invented”.

This brings us the works of Silva Özyerli, an Armenian living in Istanbul known for her books on culinary culture. Özyerli, whose family roots trace back to the historical city of Diyarbakir, known as Dikranagerd or Amida in Armenian, spent her childhood and early youth in this city. In her first book, Amida’nın Sofrası (Amida’s Table), published in 2019, she not only proved herself as an author but also won the Best Book of the Year award in the Gastronomy category from Dünya newspaper. In this book, Özyerli tells her family’s story along with the ancient dishes cooked in the Christian households of Diyarbakir – dishes, many of which are now forgotten.

Özyerli’s latest book, Amida’nın Ruhu (Amida’s Spirit), delves into the liqueurs that are an integral part of the dining culture, especially during celebrations in Diyarbakir. She combines the production of liqueurs from a variety of fruits and plants – from cherries to chestnuts, chocolate to roses, bergamot to melons – with old Diyarbakir stories, illustrating the rich cultural heritage that could have been preserved if the Armenians of Anatolia had not been dispossessed and had continued living on their lands. However, liqueur, considered a product of refined taste, was typically associated with upper class Istanbul culture, even among Armenians. Özyerli’s work on Diyarbakir liqueurs, especially her tasting events, talks, and workshops held before the book’s release, demonstrate that Anatolian Armenians were as familiar with liqueur as those in Istanbul, if not more. This reminds us that our stereotypes about Armenian identity are bound to be flawed.

In Turkey, food often becomes a matter of national pride and sometimes a source of tension with other nations. In a country on a belated but sharp path to nationhood, the “Turkishness” of culinary products like baklava, lahmadjo, and kokorech is emphasized and persistently sought to be registered as “national”. However, attributing the rich culinary and historical flavors of a multi-ethnic and multicultural geography to a single nation would obscure the truth. In today’s Turkey, the bearer of the legacy of the Ottoman Empire, for those who wish to see it, it is easy to see traces of this plurality on both everyday and elite tables. Özyerli’s works are just one example of this.

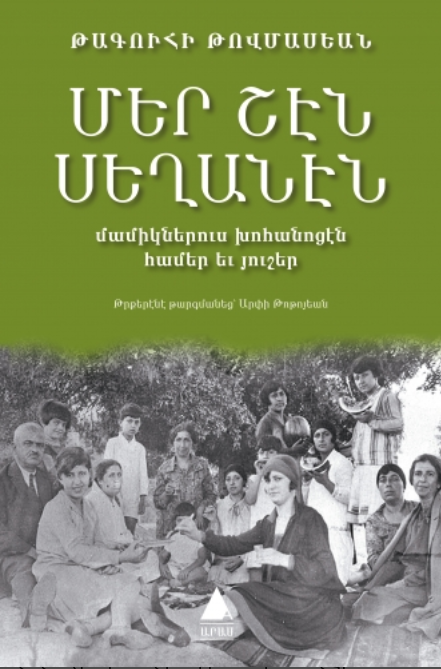

Her work builds on the foundation laid by another book celebrating its twentieth anniversary today. Sofranız Şen Olsun (May Your Table Be Joyful) by another Turkish Armenian, Takuhi Tovmasyan, presented the dishes of her Istanbul and Thrace-rooted family, blending them deliciously with family stories. Her work, categorized as “memoir-cuisine,” opened the door wide for Özyerli and others, highlighting the often-overlooked domestic female labor and contributing invaluable insights into the shared culture with hidden culinary treasures.

Takuhi Tovmasyan and Silva Ozyerli

Özyerli and Tovmasyan are not alone in their efforts to uncover hidden stories related to food. Marianna Yerasimos, from a Turkish Greek family, has left a significant mark in the field of culinary culture and history with her research on Ottoman palace cuisine, the meals mentioned in the travelogue of 17th-century Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, and her grandmother’s kitchen in the Cappadocia region. Another Greek researcher, Meri Çelik Simyonidis, brings together the stories and recipes of people from different cultures who added flavor to Istanbul’s tables. Lian Penso Benbasat, aiming to preserve the culinary traditions of the Sephardic Jews who migrated from Spain to the Ottoman lands in the late 15th century, shares these traditions through her YouTube video series “Köklere Dönüş” (Return to Roots) and her writings. Ayşe Kudat, with her book Kürt Mutfağında Ne Pişiyor? (What’s Cooking in the Kurdish Kitchen?), focuses on the culinary creations of the Kurds in Turkey, a population large in number but deprived of many rights, highlighting their resilience and continued production of flavors despite hardships. Anna Maria Beylunioğlu, belonging to the Arab Orthodox community of Antakya, the historical Antioch, through her academic work, reveals the multilayered structure of Ottoman-Turkish cuisine and fights against homogenization. Levon Bağış, a sought-after name for wine workshops and the owner of a prominent bistro in central Istanbul, combats nationalist and conservative narratives by educating the new generation of Turks, who grew up with monolithic historical stories, about the richness of Anatolia and the ancient Armenian lands, the birthplace of wine.

These individuals and their work remind us of the vibrant and diverse history that was intended to be forgotten through massacres, forced migrations, and a history of violence. Özyerli, Tovmasyan, Yerasimos, Simyonidis, Benbasat, Beylunioğlu, Bağış, Kudat, and many others strive tirelessly to remind us that there is a place for all peoples and all of humanity under the sun, and the land we live on once produced various flavors for all its inhabitants. They carry in their hearts the longing for the days when we will be “among friends, at the table of the sun” as in the words of poet Nazım Hikmet.

Rober Koptaş is a writer and publisher, lives in Istanbul. He served as the editor-in-chief of Agos newspaper from 2010 to 2015 and the general director of Aras Publishing from 2015 to 2023.

2 Comments

Love this and all your articles Rober!

Today, as in the past, the phenomenon of eating is accepted as a cultural element by society. Mr. Koptaş wrote the sociology and history of food and he did them very well. thanks…